Spirituality and Religion in Europe

For some years, a number of scholars, such as Linda Woodhead and Paul Heelas (2005) and David Tacey (2000), have been arguing that the world, or at least the Western world, is going through a spiritual revolution. People are embracing 'spirituality' rather than 'religion'. Recent research has enabled critical evaluation of this claim.

The Extent and Nature of the Affirmation of Spirituality in Europe

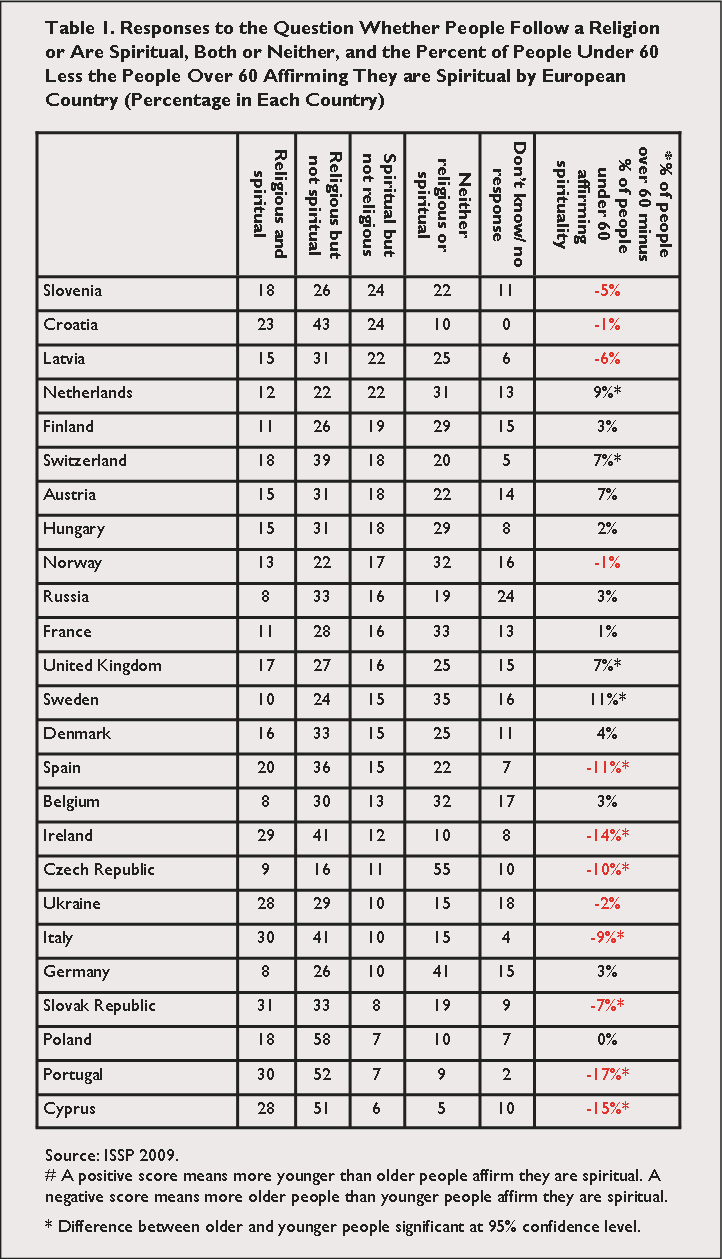

The International Social Survey Program conducted in 44 countries during 2008/2009 included a number of questions on spirituality and religion. In one of these questions people were asked whether they described themselves as religious and spiritual, religious but not spiritual, spiritual but not religious or neither. Table 1 summarises the responses to this question for each of the 24 European countries in the study. It shows that the proportion of people who identify themselves as spiritual but not religious varies from 24 per cent in Slovenia to 6 per cent in Cyprus.

This question about being religious or spiritual has not been asked before in a large survey program such as this. Thus, it is not possible to ascertain the trends by comparing it with other surveys completed at different periods of time. However, some indication of probable trends can be identified by comparing older and younger people. Assuming that comparatively few people change their sense of being religious or spiritual over time, a comparison of the responses of older people and younger people may give us some idea of how changes in culture are occurring.

A comparison of the responses of under and over 60s shows that in every country in Europe, older people are more likely to describe themselves as religious. In Croatia and Austria, the differences are not significant at 95 per cent level, but in every other country, the differences are significant, indicating a decline in people following a religion.

However, the patterns are quite different in relation to spirituality as shown in the final column of Table 1. In 12 countries, more younger people than older people saw themselves as spiritual. In 11 countries, more older people than younger people saw themselves as spiritual. In one country, Poland, there was no difference between older and younger people. It should be noted that in 14 countries out of the 24, the differences between older and younger people were not significant at the 95 per cent confidence level (no asterisk).

It will be noted that there is a tendency for the higher numbers of younger 'spiritual' people to be found in the northern countries of Europe with a Protestant history. The lower numbers of younger spiritual people are found mostly in the Catholic and Orthodox countries of south and eastern Europe.

Further analysis has shown that in most of the countries where spirituality is less among younger people, it is associated with belief in a personal God. In other words, in these countries, spirituality is understood in terms of personal devotion, or belief in the supernatural powers of God. In those countries where spirituality is found more among younger people, it is usually associated with belief in a higher power or spiritual forces in nature, rather than with a personal God. In other words, 'spirituality' means quite different things in different countries and there is no one 'spiritual revolution' across Europe.

What is evident is that in a number of countries in northern Europe where there is a Protestant heritage and in which the making of meaning is approached more individually, there are more young people than older people embracing spirituality as something individual and associated with higher powers rather than with the God of religious institutions.

The Origins of 'The Spiritual Revolution' in Northern Europe

It is highly likely that the northern European kind of spirituality has its roots in the individualism of post-modernity that has arisen from those types of child-rearing that emphasise meeting the needs and interests of each individual child rather than focussing on the wellbeing of the whole family. This has been shown to be connected to the reduction in family size and changes in technology in the home which allowed greater attention to the needs of individual children in the 1960s and 1970s (Berger et al, 1974). Along with other social processes such as an increase in the pluralism of beliefs and life options that came through migration, world travel and television in the 1960s and 1970s, there was a significant change in the way people sought meaning in life.

Heelas and Woodhead (2005) have argued that, prior to the 1960s, meaning was primarily sought through the fulfilment of those roles which one had inherited through birth or through one's social situation. Married women sought meaning, for example, in fulfilling the duties of being a good wife and a good mother. Men sought meaning in providing economically for their families. Both men and women sought meaning in fulfilling the duties of the religion which they inherited by birth. Such a sense of finding fulfilment by fulfilling one's duties in life is still common in the southern and eastern European countries. Most southern and eastern Europeans have a strong sense that their religious identity is given to them by birth and that being a good person means fulfilling those religious duties.

However, children who grew up after the 1960s when thinking about their own needs and interests looked for fulfilment in what Heelas and Woodhead call their 'subjectivity'. Life consisted in finding what was personally fulfilling, what gave a sense of personal authenticity, rather than the fulfilment of external duties laid upon them by birth or their social situation. It is in this situation that many have turned away from the traditional duties of religion and have sought meaning in the spirituality which they have personally constructed for themselves. In the terms of the social theorist, Anthony Giddens (1991), life came to be lived more reflexively, as a constantly developing biography, rather than as a fulfilment of a specific set of duties and responsibilities.

'Spirituality' means a great many things to different people. But common characteristics include the fact that it is seen as developed and owned individually rather than by institutions. It is often developed from a range of sources rather than one particular source. It is found expressed in the recounting of experience rather than in expression of dogma. It tends to focus on this life rather than the next, and is oriented towards human wellbeing rather than towards a transcendent God (Fisk, quoted in Geels 2009).

The Implications of The Spiritual Revolution for Mission

The development of such forms of individualised spirituality in Western Europe has many important implications for how mission is conducted in those places. There are a number of features of contemporary spirituality which many Christians can affirm, and, indeed, in some of those features there may be helpful correctives for some ways in which Christianity is expressed.

Firstly, contemporary spirituality recognises that there is 'something beyond' this material world. A number of commentators, such as Antoon Geels (2009), have noted that many forms of contemporary spirituality recognise the mystery in human life and in the universe as a whole. It is, in part, a protest against reducing the world to that which is material and mundane. Geels argues that this sense of mystery is very much in line with that described by the mystics of many religions including those in the Christian tradition. The recognition of mystery in contemporary spirituality may be an important antidote to the Protestant tendency to anthropomorphise God, as Karen Armstrong (1993) has argued.

Contemporary spirituality also reminds people of the fragility of the earth and the need for its care. It reminds Christians of the important of recapturing respect for creation and dedicating themselves to its care. Associated with the sense of the mystery of God is the emphasis on the experience of God. Again, this fits with many Christian traditions, and has been a feature of the Pentecostal and charismatic churches.

“To put it in Jesus’ terms: the purpose of Christian mission is to call people to love God and to love their neighbours as themselves.”

Where Christians need to make a stand over against some forms of contemporary spirituality is in arguing that such fulfilment in life is not found primarily by focussing on self-realisation or obeying one's inner impulses, as Heelas and Woodhead seem to suggest, but through one's contribution in relationship with others. In contemporary society, each individual can develop their own biographies but they will not find those biographies meaningful until they make their own personal contributions to the lives of others and to the wider society. Ultimately we find fulfilment in life when we focus on the wellbeing of others and not just ourselves.

To put it in Jesus' terms: the purpose of Christian mission is to call people to love God and to love their neighbours as themselves. Love of self, love of our neighbour - not only our friends and relatives but also the members of wider society – and love of God is the spirituality to which Jesus calls us.

Contemporary spirituality can remind us that Jesus' call is to relationship. It is not primarily a call to church attendance, even though that may be a significant basis for relationships with others. We are likely to see increasing numbers of people looking for ways in which they can explore faith or express faith through short-term activities such as involvement in social welfare or social justice activities, through music and drama, through small groups and large festivals, rather than through the weekly congregational worship. We may still want to uphold weekly congregational worship as part of the nature of the church, but we may need to see it as the end of a path, rather than the start of an exploration for the love for God, for one's neighbour and one's self.

Philip Hughes, Christian Research Association, Australia

References:

Armstrong, K., A History of God. London: Random House, 1993.

Berger, P., Berger, B. & Kellner, H., The Homeless Mind. London: Pelican Books, 1974

Geels, A., "Glocal Spirituality for a Brave New World." In Postmodern Spirituality, edited by Tore Ahlback and Bjorn Dahla. Abo, Finland: Donner Institute for Research in Religious and Cultural History, 2009.

Giddens, A., Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1991.

Heelas, P. & Woodhead, L., The Spiritual Revolution: Why Religion Is Giving Way to Spirituality. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2005.

Tacey, D., The Spiritual Revolution: The Emergence of Contemporary Spirituality. Sydney: Harper Collins, 2003.

Data Source

International Social Survey Program (2008-2009) http://www.issp.org/