The Value(s) of Europe

“Europe’s rich spiritual and cultural history – combining elements of Antiquity, Judaism, Christianity, Islam, the Renaissance and the Enlightenment - has created an array of indisputable values, to which the European Union pays lip service, but which it often regards simply as pretty packaging for the things that really matter. But aren’t these values what really matter, and are not they, on the contrary, what give direction to all the rest?”

Vaclav Havel, European Parliament, 2009

The importance of the place of values in Europe continues to be a matter of furious debate, as evidenced by this quote from the recently deceased former Czech President, Vaclav Havel. Are there any values which might be described as characteristically European? Or is Europe so culturally diverse, that any talk of common values is to fly in the face of nationalisms and regionalisms which define their identities over and against Europe?

Over the last few editions of Vista we have made regular use of statistics from The European Values Study (EVS). In November 2011 sociologists from across Europe gathered for The Value(s) of Europe Conference at Tilburg University in the Netherlands to present their findings from the 2008 wave of research. At the conclusion of the conference the Atlas of European Values was published.

The Atlas, together with the accompanying website, www.atlasofeuropeanvalues.org provides a unique insight into the values and attitudes of today’s 800 million Europeans. Given its scope and significance, we wanted to dedicate the best part of this issue of Vista to setting out the data under the themes of family, work, society, politics and religion.

Family

The family is one of the domains where the greatest changes have taken place over recent generations. The traditional nuclear European family consisted of a married father and mother with a several children but today this is now only one option among many. Declining marriage rates, an increased number of divorces, the wide acceptation of co-habitation, the legalization of same-sex marriage and dropping fertilityrates have caused the size of the average household within the European Union to drop to 2.4 people. The roles of men and women have changed, with women in most European countries enjoying broadly the same educational and employment opportunities as men. Have these changes in family composition and roles resulted in a dramatic change of values? Yes and no. The data from the EVS does not support the claim that there has been a revolutionary transformation in family values. The results indicate that the demise of traditional values has been exaggerated. Family remains of the utmost importance to people. 84 percent of Europeans say that family is very important, almost twice as much as the number of people who find friends very important. (Figure 1)

However there are some noticeable changes. The acceptance of single mothers has risen sharply since 1990 with countries which showed early willingness to accept single-motherhood like Iceland and Denmark, being joined by countries such as Spain, Lithuania and Croatia, all traditionally Catholic. In the majority of European countries most people do not reject couples living together without being married.

Perhaps the most significant changes relate to childbearing since these result in important demographic changes over time, an issue which Darrell Jackson deals with later in this edition of Vista. Throughout Europe, having children is no longer considered a duty towards society but rather one of life’s options. The choice of staying childless is well accepted in many countries.

The driving force behind these changes appears to be individualization: “Values oriented toward autonomy, privacy, selfactualization and personal happiness have become more important and oust values that point at collective goals. A good illustration of this process is the fact that obedience is losing ground as an important quality for children to acquire at home, while independence is gaining ground.” Atlas of European Values, p.35

Missional Reflection

That today’s Europeans continue to value family ahead of friends, work, leisure time, politics and religion as the most important thing in their lives, should make us stop and think. Despite the increased orientation of life values towards the individual the family is still hugely important to most people. Mission innovation over the last decade has focussed on developing networks and communities that can meet the consumerist tendencies of contemporary society. Perhaps it is time to consider again what “mission to families” might mean in 21st Century Europe.

Work

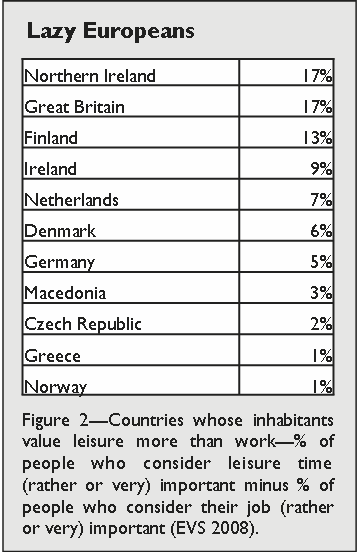

58 per cent of Europeans say that work is very important in their life, only surpassed in significance by the importance of family. However, the importance of work is often inversely correlated to wealth: in the wealthier countries, work is considered of less importance, a means to an end rather than an end in itself (Figure 2).

The conviction that work is a virtue is predominantly found today in the countries of Eastern Europe, namely Kosovo, Bulgaria and Turkey. The weakest sense of work ethic is currently to be found in Iceland Great Britain, Sweden and the Netherlands. Maybe it is time to consign the concept of “Protestant work ethic” to the history books. Interestingly, there has also been a notable decline in work ethic in Poland over the past twenty years, despite their reputation as hard and skilled workers. Is this the contagious effect of their emigration to formerly Protestant countries?

Missional Reflection

It goes without saying that the economic crisis in Europe will have markedly affected the attitudes and values of Europeans since 2008 when the EVS was conducted. Almost certainly if the same survey was conducted today, the percentages of those considering work to be important would be higher, even or perhaps especially, in the (formerly) wealthier countries of Western and Northern Europe. The challenge of engaging in mission in a context of crisis and insecurity will be the subject of the next edition of Vista.

Society

This summer’s riots, together with the immoral behaviour of City bankers and Premiership footballers, were seen by journalists as evidence of a widespread moral decay in Britain. What indicators are there in the European Values Study that morality is breaking down?

Europeans appear to be quite clear in their rejection en masse of lying in your own interest, cheating on tax returns or avoiding a fare on public transport. However, a closer inspection of the data raises serious questions about the honesty of those who might be dishonest! Most Europeans consider that it is (almost) never justified to cheat on your tax return but the unreliability of this statistic is highlighted by the fact that the country which is most willing to countenance tax evasion is the Netherlands! This says more about the honesty of the Dutch (even when they are confessing to dishonesty) than it does about the rest of Europe.

There is a North-West/South-East divide in regard to the trust that Europeans have in other people. Norway, Denmark, Iceland and the Netherlands show the highest levels of mutual trust, whereas the most distrusting people live in Cyprus and Turkey. Francis Fukuyama observed that economic development and government performance were linked with levels of trust and this appears to be borne out in the EVS: the most trusting Europeans tend to live in prosperous countries. However, there are exceptions. Austria, Luxembourg and Belgium show lower levels of trust than their wealth would suggest.

For many years Europe has been a magnet for immigration. It is estimated that there may be as many as 70 million immigrants across the whole of Europe. What can be stated with more confidence is that there are 32.5 million foreign citizens living in the EU27 member states of which 12.3 million were citizens of another EU27 member state and the remaining 20.2 million were citizens of countries outside the EU27. (Source: Eurostat, Statistics in Focus, 34/2011 http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/ cache/ITY_OFFPUB/KS-SF-11-034/EN/KS-SF- 11-034-EN.PDF)

Attitudes to immigrants vary widely across Europe according to the EVS. Immigrants are not very welcome in countries like Malta, Hungary, Georgia, Cyprus, Northern Ireland and Great Britain. Less than a third of the population in these countries say that people from less-developed countries are always welcome, or that they are welcome as long as jobs are available.

Many Europeans believe that immigrants take jobs away from native people. Only the Scandinavians and Luxembourgers disagree with this view. More interesting is the divergent attitude to assimilation. People living in Western Europe and Scandinavia generally feel that immigrants should assimilate, that is, they should adopt the customs of their new home country. In contrast, in Cyprus, Romania, Greece, Bulgaria, Kosovo, Serbia and Albania, that is to say, in southeastern Europe, the prevailing attitude is that it is better for the greater good of society that migrants maintain their distinct customs and traditions.

Europeans seem generally convinced that an environmental catastrophe is just around the corner. In all countries, a majority of the people believe that an ecological disaster cannot be prevented. The Dutch are the most optimistic having only 60% of doommongers, but on Cyprus it is almost impossible to find anybody who thing things will turn out well environmentally – 98% of islanders believe that disaster is ahead.

Missional Reflection

What challenges do divergent attitudes about migrants pose to European mission? Integration of migrants is not seen as desirable in every country yet surely they are precisely the places where the radical challenge of Galatians 3:28 must be heard: There is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus. Conversely in Western Europe where the expectation is of integration, the churches needs to respect and value the cultural autonomy of migrant churches whilst supporting them practically and building relationships which might help them to feel welcome.

Is not the universal ecological pessimism across Europe also an opportunity for the church to speak out on environmental issues? As economic realities cause politicians to put environmental considerations to one side, is it not the moment for the church to seize the initiative and show in word and deed that Christian mission also involves the stewardship of God’s creation.

Politics

Support for democracy as the best form of government is strong in Western Europe but the further one travels to the East the less support there is for democracy. This doesn’t imply that people are content with the current political systems. Only those living in Scandanavia, the Netherlands, Ireland and Switzerland are overwhelmingly positive about the political status quo. Surprisingly, they are accompanied by Kosovo and Belarus, the latter often considered to be the last dictatorship of Europe. It may be that respondents in Belarus were not entirely honest in their replies, but perhaps the widespread support for authoritarian leadership in Eastern Europe is a better explanation.

Support for alternative forms of government, either by technocrats or a “strong man” is significant. Both within and without the EU27 a majority of citizens are in favour of establishing a technocracy: a rule of experts instead of a government. And in the non-EU countries almost 60% of people favoured a “strong man” to rule the country: a leader who does not bother too much with parliament. Only a quarter of EU27 respondents support the idea of a “strong man” in charge.

Missional Reflection

Cross-cultural church planters must bear in mind that the forms of church government that they seek to establish bear the marks not only of their theological convictions but also the culture in which their church developed. The expectations in Eastern Europe (and to some degree Southern Europe too) are that leaders must be dominant and authoritarian. A more democratic style of church government will be seen to be weak and ineffectual. In Western and Northern Europe the opposite is true, but should we just take our lead from the culture, or rather seek to transform these leadership paradigms from within?

Religion

Previous editions of Vista have featured our own analysis of the EVS data relating to secularization and religiosity in Europe. Nevertheless it is interesting to observe that other sociologists of religion are noting exceptions to the secularization thesis which predicts a universal decline in religiosity as modernization progresses.

More than 90% of the people in Albania, Cyprus, Belarus, Georgia and Kosovo claim to be religious, but even in supposedly secularized countries like Netherlands and Denmark, the majority of people say the same. The majority of Europeans continue to consider themselves members of a church and conversely atheism is strikingly rare. France has the most atheists but even then it only represents 18% of the population.

Grace’s Davie coined the phrase “believing without belonging” to describe the religious experience of many Europeans. In the Czech Republic, the Netherlands and Estonia many people say they are religious but they do not practice their religion in any traditional sense, perhaps reflecting the increased individualization of society. In other countries such as Sweden, Norway, and Switzerland the opposite is the case, as the number of people belonging to a church is much higher than the number saying they are religious. This alternate practice of “belonging without believing” seems to prevail in those countries where church membership is linked with citizenship and a sense of national identity. Nevertheless, the EVS data demonstrates that today’s Europeans continue to value religious services at special occasions. Nearly 70% value a religious marriage ceremony and 80% want a religious service at their funeral (Figure 4). Even in markedly secularized countries like France the percentages are mainly stable especially in the case of death (Figure 5).

So much for religious identity, but what about beliefs? It is here we observe some of the more striking contours of the European religious landscape:

The idea that there is only one true religion can only count on a majority of support in the Muslim countries of Turkey and Armenia.

In Turkey and Malta belief in heaven and hell is unquestioned, but in Denmark and Sweden and also in Spain and Portugal scepticism about their existence prevails.

All over Europe, more people believe in heaven than in hell.

Belief in lucky charms and talismans prevails in Romania, Greece and Moldova, whereas in Finland, Norway, Denmark, Netherlands and surprisingly Italy, the people are much more sceptical about the efficacy of such things.

Missional Reflection

Both these results and our own work on the youngest cohort suggest that many European countries are becoming increasingly secularized. However, there is some evidence, and our findings were not refuted when we presented them at the Value(s) of Europe Conference in Holland, that there is a bounce in religiosity amongst the young in certain countries.

The reality is that religious belief continues to be very important for many Europeans. Sociologists like David Voas have suggested that we might characterize European religiosity as “fuzzy fidelity” in that it is diffuse and often contradictory— belief and practice don’t necessarily correlate with each other. Yet Europe is not the secular bulwark that some journalists would have us believe. The Christian memory of Europe is just about intact still, and in fact the younger generation may be more open to a fresh presentation of the Christian gospel than we might think.

Jim Memory